North America

Europe

Latin America

Asia Pacific

Africa

Middle East

North America

Europe

Latin America

Asia Pacific

Africa

Middle East

В сердце Alltech лежит путешествие в мир предпринимательства.

В 1970-х годах наш основатель и президент, доктор Пирс Лайонс, переехал в Соединённые Штаты с мечтой: сохранить нашу планету и жизнь на ней. Будучи учёным ирландского происхождения, он разглядел возможность применить свои знания в области ферментации дрожжей для решения проблем кормления животных, и его мечта стала реальностью, когда в 1980 году он основал Alltech с начальным капиталом всего $10,000.

Сегодня, коллектив, насчитывающий более 6 000 человек по всему миру, разделяет его взгляды на способы поддержки и обеспечения питанием растений, животных и людей.

Мы воплощаем в жизнь его идеи, улучшая качество растений, кормов и продуктов питания при помощи кормления и новейших научных знаний, в частности, в области технологий, связанных с дрожжами. Наша команда стремится помочь растениям и животным полностью раскрыть свой потенциал, при этом также помогая производителям улучшить эффективность, прибыльность и устойчивость.

Наш ведущий принцип

Нашим ведущим принципом является принцип ACE, в соответствии с которым продукты компании должны быть безопасны для Животного (Animal), Потребителя (Consumer) и Окружающей среды (Environment).

В сердце Alltech лежит путешествие в мир предпринимательства

В 1970-х годах наш основатель и президент, доктор Пирс Лайонс, переехал в Соединённые Штаты с мечтой: сохранить нашу планету и жизнь на ней. Будучи учёным ирландского происхождения, он разглядел возможность применить свои знания в области ферментации дрожжей для решения проблем кормления животных, и его мечта стала реальностью, когда в 1980 году он основал Alltech с начальным капиталом всего $10,000.

Адрес

223053, Беларусь, Минская обл., Минский р-н, д. Боровая, д.1, офис 420

Телефон

+(375) 17 357 99 28

Факс

+(375) 17 357 99 28

Alltech® Café CitadelleAlltech® Café Citadelle – это «чаша надежды» для Гаити. После разрушительного землетрясения в 2010 году основатель Alltech доктор Пирс Лайонс поставил цель создать там устойчивое предприятие с местной жемчужиной: выращенным в горах на 100%, органическим, имеющим сертификат Справедливой торговли (Fair Trade Certified™) кофе арабикой. Мы продвигаем на рынке и продаём эти кофейные зёрна как Café Citadelle и используем их при приготовлении нашего пива Kentucky Boubon Barrel Stout®. Вся прибыль от продажи Café Citadelle поступает обратно в Гаити, где реинвестируется в две начальные школы на севере Гаити. |

|

|

Винокурня Пирса Лайонса в Сейнт ДжеймсеБогатая семейная история, личная страсть к пивоварению и винокурению, а также предпринимательский дух привели к созданию в Дублине предприятия, производящего изысканный ирландский виски, винокурни Пирса Лайонса в Сейнт Джеймсе, Pearse Lyons Distillery at St. James. Основанная доктором Пирсом и миссис Дейдрой Лайонсами, эта винокурня воссоздаёт историю. Пять поколений предков Пирса Лайонса были бондарями, поставлявшими бочки на многие винокурни Дублина. У Пирса Лайонса была степень доктора наук в области дрожжевой ферментации. Он стал первым ирландцем, получившим официальную степень в области пивоварения и винокурения в Британской школе солода и пивоварения. Во время обучения в университете он стажировался на пивоварнях Guinness и Harp Lager, а затем работал биохимиком в Irish Distillers. С целью сохранения присущего винокурне Пирса Лайонса уюта, экскурсии проводятся для небольших групп. Радушные гиды делятся с посетителями захватывающими историческими рассказами, восходящими к 12 веку. |

ПРАВИЛЬНАЯ СМЕСЬ ДЛЯ КОРОВ КАЖДЫЙ ДЕНЬ

Кормораздатчики KEENAN® имеют уникальную систему смешивания кормов.

О KEENAN

Компания KEENAN является признанным лидером в области инновационных и прибыльных сельскохозяйственных решений, направленных на максимальную эффективность кормления. KEENAN основана в Ирландии в 1978 году. Штаб-квартира компании расположена в графстве Карло, Ирландия. В течение почти четырех десятилетий в бизнесе компания завоевала репутацию производителя высококачественных современных кормосмесителей.

На сегодняшний день машины KEENAN представлены в более чем 70 странах мира.

Работая в Alltech, мы понимаем, что выращивание высококачественных, здоровых и эффективных животных – это непростая задача, поэтому наша поддержка не ограничивается кормлением.

Alltech устанавливает партнёрские отношения с производителями по всему миру, чтобы помочь им достичь поставленных целей, выявить проблемы и заложить фундамент для прибыльного и устойчивого будущего. Имея почти сорокалетний опыт в проведении исследований, продукты с доказанной на практике эффективностью и команду квалифицированных экспертов, Alltech может помочь вам в повышении эффективности, продуктивности и прибыльности.

Благодаря проводимым нами новейшим исследованиям в области нутригеномики, предлагаемые нами кормовые технологии помогают животным максимизировать использование питательных веществ корма для достижения оптимального общего состояния и продуктивности.

Мы работаем с производителями по всему миру, чтобы решать наиболее важные для них проблемы, включая конверсию корма, производство без антибиотиков, обогащение продуктов питания, менеджмент микотоксинов, здоровый кишечник, использование белка, ферментов и минералов.

Например, наши технологии, направленные на улучшение здоровья кишечника, подтверждены более чем 730 опытами. Поскольку законодательство в области применения антибиотиков повсеместно ужесточается, мы готовы предложить решения с доказанной на практике эффективностью для улучшения здоровья кишечника и общего состояния животных.

>

Получайте конкурентное преимущество за счёт использования наших аналитических услуг на ферме:

Подбор квалифицированных сотрудников продолжает быть трудной задачей для фермеров по всему миру. Alltech может провести семинары для вашей команды, помогая вам добиться выполнения всеми сотрудниками одинаковых протоколов и мероприятий и понимания ими причин, лежащих в основе этих действий.

Жизнь – это постоянное обучение.

Обучение – это путешествие длиною в жизнь, и мы ставим своей целью взращивание любопытства и стимулирование инноваций. Только таким образом мы сможем справиться с грядущими вызовами.

В Alltech мы инвестируем в будущее при помощи создания научных лабораторий, глобальных конкурсов в области искусства и науки, а также уникальных карьерных возможностей для профессионалов.

Каждый день несёт в себе возможности для открытий.

Программа «Молодой учёный Alltech» - крупнейший мировой конкурс в области сельскохозяйственных наук. Конкурс призван объединить ярчайшие молодые умы из колледжей и университетов всего мира и даёт возможность получить награды за научные исследования и открытия, соревнуясь на высочайшем международном уровне.

Alltech содействует стремлению студентов найти новые решения в области здоровья и кормления животных, растениеводства, новых аналитических методов в сельском хозяйстве, безопасности производственной цепи, здоровья и питания человека и в других смежных областях сельскохозяйственной науки, а также получить бесценный опыт работы в международной команде.

Инновации лежат в самом сердце созидания и перемен. Этим обусловлена страсть Alltech к разнообразию бизнес-интересов, созданию глобальной команды сотрудников, науке и разработке новых решений. В этом заключается идея конкурса инноваций Alltech.

Конкурс инноваций Alltech впервые прошёл в 2013 году в Кентукки и Ирландии. В рамках конкурса студенты и выпускники университетов разрабатывают прогрессивные бизнес-планы на основе инновационных идей в области кормления животных, растениеводства, пищевой промышленности, а также пивоварения и производства алкогольных напитков, способные положительно повлиять на местную экономику. Этот конкурс, ставший ежегодным, чествует предпринимательство и влияние многофункциональных команд сотрудников на развитие бизнеса.

Предприятия-победители получают награду в $10,000*. Это как раз та сумма, с которой доктор Пирс Лайонс основал Alltech, компанию, нынешний оборот которой составляет почти $2 миллиарда.

Программа развития карьеры Alltech – это отличная возможность для высокомотивированных выпускников, желающих построить головокружительную карьеру.

Alltech, мировой лидер в области кормления и здоровья животных, предлагает и обеспечивает реализацию большого количества инновационных решений, устанавливающих новые стандарты для надёжного будущего. Мы заинтересованы в присоединении энергичных и инициативных людей к нашему многомиллиардному бизнесу.

Успешные кандидаты получат возможность работать вместе с профессионалами Alltech для того, чтобы повысить продуктивность животных и растений, улучшить здоровье человека через питание и научные инновации, а также увеличить прибыльность ферм по всему миру.

Мы ищем талантливых людей, которые помогут нам развиваться, разрабатывать новые технологии и внедрять в практику исключительные стандарты качества и продуктивности. Вхождение в нашу глобальную команду открывает двери в перспективное будущее!

1. Общие положения

1.1. Настоящая Политика описывает политику ООО «Оллтек» в отношении обработки и защиты персональных данных посетителей сайта http://alltech.com/russia.

1.2. Политика информирует вас, посетителей сайта, об общих принципах и порядке обработки персональных данных, используемом ООО «Оллтек», а также о том, какие меры применяются по обеспечению безопасности ваших персональных данных. Политика также содержит информацию о ваших правах и способах их реализации.

1.3. Целью Политики является обеспечение защиты прав и свобод человека и гражданина при обработке его персональных данных, в том числе защиты прав на неприкосновенность частной жизни, личную и семейную тайну.

1.4. Политика применяется к посетителям сайта в тех случаях, когда к отношениям с ними применяется законодательство Российской Федерации. Политика разработана в соответствии с положениями Федерального закона Российской Федерации от 27.07.2006 №152-ФЗ «О персональных данных», а также иными нормативными правовыми актами Российской Федерации, устанавливающими требования к обработке персональных данных.

1.5. ООО «Оллтек» может вносить изменения в Политику. Дата последнего изменения будет указываться в пункте «Дата вступления в силу», которая будет обозначать дату вступления Политики в силу в новой редакции. Пункт «Версия Политики» должен быть изменен соответствующим образом.

1.6. В настоящей Политике используются термины и определения, предусмотренные действующим законодательством, а также следующие:

Политика - Политика ООО «Оллтек» об обработке персональных данных посетителей Сайта.

Оператор - юридическое лицо ООО «Оллтек», юридический адрес: 105062, г. Москва, Подсосенский переулок, д. 26, стр. 3, этаж 2, самостоятельно или совместно с другими лицами организующее и (или) осуществляющее обработку персональных данных, а также определяющее цель обработки персональных данных, состав персональных данных, подлежащих обработке, действия (операции), совершаемые с персональными данными.

Сайт - Сайт в информационно-телекоммуникационной сети «Интернет», доступный по ссылке http://alltech.com/russia.

Обработка персональных данных - любое действие (операция) или совокупность действий (операций), совершаемых с использованием средств автоматизации или без использования таких средств с персональными данными, включая сбор, запись, систематизацию, накопление, хранение, уточнение (обновление, изменение), извлечение, использование, передачу, обезличивание, блокирование, удаление, уничтожение персональных данных.

Персональные данные - любая информация, относящаяся к прямо или косвенно определенному или определяемому физическому лицу (субъекту персональных данных). Перечень персональных данных, которые обрабатываются Оператором, указаны в пункте 5.1 настоящей Политики. Субъект персональных данных - посетитель Сайта. Закон о персональных данных - Федеральный закон Российской Федерации от 27.07.2006 №152-ФЗ «О персональных данных».

2. Информация об Операторе

2.1. Компания Alltech, основанная в 1980 году ирландским предпринимателем и ученым, доктором Пирсом Лионсом, специализируется на разработке экологичных научных решений для насущных проблем сельскохозяйственной и пищевой индустрии. Alltech - ведущий производитель дрожжевых добавок, органических микроэлементов, кормовых ингредиентов, добавок и кормов. Alltech обладает опытом ферментации дрожжей, твердофазной ферментации и пищевой геномике.

2.2. Головная компания ООО «Оллтек»расположена по адресу 3031 Catnip Hill Road, Nicholasville, Kentucky 40356, USA. Европейская штаб-квартира расположена в All-Technology (Ирландия) Limited Alltech Bioscience Center, Summerhill Road, Sarney, Dunboyne Co. Meath.

2.3. «Оллтек» Инк. (далее «Компания») состоит из различных юридических лиц, включая Общество с ограниченной ответственностью Оллтек, которые формируют группу компаний (далее «Группа Оллтек»). Настоящая политика об обработке персональных данных написана от имени Группы Оллтек. Детали здесь http://alltech.com/russia. Когда мы упоминаем «Оллтек», «мы», «нас» или «наше» в настоящей политике об обработке персональных данных, мы имеем в виду соответствующую компанию Группы Оллтек, которая несет ответственность за обработку ваших персональных данных. Настоящая политика применима ко всем сайтам Оллтек и компаниям, которые имеют ссылку или упоминание на политику об обработке персональных данных.

3. Цель обработки персональных данных

3.1. Обработка персональных данных ограничена достижением конкретных, заранее определенных и законных целей. Обработка персональных данных, несовместимая с целью обработки, указанной в п. 3.2 настоящей Политики, не допускается.

3.2. Целью обработки персональных данных Оператором является обеспечение взаимодействия Оператора с Субъектами персональных данных, что подразумевает следующие возможные случаи использования персональных данных: предоставление ответов на запросы Субъектов персональных данных, в том числе, о продуктах и (или) услугах Оператора; предоставление информации об услугах Оператора, публикаций и маркетинговых материалов; обеспечение участия в конкурсах, акциях или исследованиях; связь с оператором по почте, электронной почте, по телефону или иными способами.

3.3. Оператор осуществляет обработку только тех персональных данных, которые отвечают заранее объявленной цели их обработки. Оператор не собирает и не обрабатывает персональные данные, не требующиеся для достижения цели, указанной в п.3.2. настоящей Политики, и не использует персональные данные субъектов в целях, отличных от заявленной выше.

4. Правовые основания обработки

4.1. Оператор обрабатывает персональные данные в случаях, когда это допускается законодательством Российской Федерации.

4.2. Правовыми основаниями обработки персональных данных являются следующие:

– согласие Субъекта персональных данных на обработку его персональных данных;

– необходимость осуществления и выполнения возложенных законодательством Российской Федерации на Оператора функций, полномочий, обязанностей;

– необходимость исполнения договора (например, публичной оферты), стороной которого или выгодоприобретателем которого является Субъект персональных данных;

– когда это необходимо для статистических или иных исследовательских целей при условии обязательного обезличивания персональных данных;

– при условии обеспечения Субъектом персональных данных или по его просьбе доступа неограниченного круга лиц к своим персональным данным;

– когда персональные данные подлежат опубликованию или обязательному раскрытию в соответствии с федеральными законами.

5. Объем и категории обрабатываемых персональных данных

5.1. При использовании Сайта Субъект персональных данных соглашается, что Оператор вправе использовать статистические данные и разные технологии отслеживания (Cookies-файлы), для их последующей обработки такими системами как при условии, что такие данные являются обезличенными.

5.2. Информация, собираемая в процессе использования Сайта: данные IP-адреса, тип и версия браузера, часовой пояс и местоположение, типы плагинов браузера и их версии, операционная система и платформа, иные технологии, которые использует Субъект персональных данных для доступа к Сайту, сведения о том, как Субъект персональных данных использует Сайт

5.3. Оператор не использует IP адрес для целей идентификации субъектов персональных данных.

5.4. Оператор не осуществляет обработку специальных категорий персональных данных, включая персональные данные, касающиеся расовой, национальной принадлежности, политических взглядов, религиозных или философских убеждений, состояния здоровья, членство в профсоюзах, личную жизнь (сексуальную жизнь), сексуальную ориентацию, а также какие-либо биометрические персональные данные. Мы не собираем какую-либо информацию об уголовных преступлениях.

5.5. В степени, допустимой законом, при обработке персональных данных Оператор праве получать данные о Субъектах персональных данных из открытых источников (например, социальных сетей). Субъект персональных данных понимает и соглашается с тем, что Оператор вправе получать и обрабатывать такие опубликованные данные. Принимая условия настоящей Политики Субъект персональных данных соглашается с тем, что он надлежащим образом проинформирован в смысле положений ч.3 ст.18 Закона о персональных данных.

6. Порядок и условия обработки персональных данных

6.1. Обработка персональных данных осуществляется с использованием средств автоматизации и / или без таковых (смешанная обработка).

6.2. Обработка осуществляется следующими способами: сбор, запись, систематизация, накопление, хранение, уточнение (обновление, изменение), извлечение, использование, передача, обезличивание, блокирование, удаление и уничтожение.

6.3. Оператор осуществляет сбор персональных данных Субъектов посредством форм, размещенных на Сайте, либо в процессе осуществления переписки по почте, электронной почте, взаимодействия по телефону или иным образом.

6.4. Сбор осуществляется в случаях, когда Субъект персональных данных:

– запрашивает информацию о продуктах или услугах Оператора;

– пописывается на наших услуги или публикации;

– запрашивает маркетинговые материалы;

– участвует в конкурсе, акции или исследовании; или

– предоставляет обратную связь или связывается с Оператором.

6.5. Помимо случаев сбора персональных данных, указанных в п.6.4. Политики сбор персональных данных Субъектов осуществляется, когда Субъекты взаимодействуют с Сайтом. Мы собираем эти персональные данные, используя cookies, о которых мы объясним в нашей политике в отношении файлов cookie.

6.6. Оператор осуществляет обработку персональных данных самостоятельно либо поручает такую обработку третьим лицам. В случае поручения обработки третьим лицам Оператор обязуется внести сведения о них в настоящую Политику, в том числе путем включения списка с помощью соответствующей ссылки.

6.7. Оператор не раскрывает третьим лицам и не распространяет персональные данные без согласия Субъекта персональных данных, если иное не предусмотрено федеральным законом.

6.8. Оператор передает персональные данные, при наличии согласия Субъекта персональных данных, следующим третьим лицам:

– лицам, входящим в группу компаний Alltech;

– бизнес-партнерам;

– поставщикам услуг;

– другим лицам и организациям по требованию закона или для защиты Оператора;

– другим лицам с согласия Субъекта персональных данных или по его указанию.

6.9. Информация о третьих лицах, указанных в п.6.6 и 6.8 настоящей Политики, публикуется Оператором на alltech.com/russia . Указанная страница в сети Интернет является неотъемлемой частью настоящей Политики. Принимая условия настоящей Политики Субъект персональных данных соглашается с тем, что он считается проинформированным о таких третьих лицах и обязуется с разумной периодичностью проверять соответствующий список.

6.10. Срок обработки персональных данных составляет 5 лет с даты предоставления согласия на обработку персональных данных.

6.11. Обработка персональных данных прекращается при наступлении следующих условий

– отзыв согласия Субъекта персональных данных;

– достижение заранее определенной цели обработки персональных данных;

– истечение срока действия согласия на обработку персональных данных;

– выявление неправомерной обработки персональных данных;

– прекращение поддержки Сайта;

– ликвидация Оператора.

6.12. Оператор уничтожает или обезличивает персональные данные при наступлении условий, указанных в п. 6.11 настоящей Политики, если иное не предусмотрено федеральными законами или договорами с Субъектами персональных данных.

6.13. Оператор вправе осуществлять трансграничную передачу персональных данных, то есть передачу персональных данных на территорию иностранного государства. Трансграничная передача осуществляется для выполнения указанной в настоящей Политике цели.

6.14. В соответствии с требованиями действующего законодательства при сборе персональных данных Оператор осуществляет запись, систематизацию, накопление, хранение, уточнение (обновление, изменение), извлечение персональных данных граждан РФ с использованием баз данных, находящихся на территории РФ.

6.15. Оператор обеспечивает конфиденциальность обработки персональных данных в порядке, установленном законодательством Российской Федерации.

6.16. В случае поручения обработки персональных данных третьим лицам или передачи персональных данных третьим лицам Оператор гарантирует обеспечение у таких третьих лиц обязанности по соблюдению конфиденциальности персональных данных, их защите и безопасности при обработке, а также с иными обязательствами, предусмотренными законодательством.

7. Хранение персональных данных

7.1. Оператор осуществляет хранение персональных данных в форме, позволяющей определить Субъекта персональных данных, в течение срока, не превышающего срока достижения цели обработки персональных данных, если иной срок не установлен федеральным законом, или договором, стороной которого или выгодоприобретателем по которому является Субъект персональных данных.

7.2. Срок хранения персональных данных не превышает срока обработки персональных данных.

8. Согласие на обработку персональных данных

8.1. Субъект персональных данных самостоятельно принимает решение о предоставлении своих персональных данных Оператору.

8.2. Субъект дает согласие на обработку своих персональных данных свободно, своей волей и в своем интересе.

8.3. Субъект выражает свое согласие с тем, что согласие на обработку персональных данных является конкретным, информированным и сознательным.

8.4. Согласие считается предоставленным, если Субъект персональных данных проставит «галочку» в форме сбора персональных данных, размещенной на Сайте для подтверждения того, что он согласен с настоящей Политикой.

8.5. В случае если согласие на обработку персональных данных Субъекта предоставляет не сам Субъект персональных данных, а его представитель, Оператор вправе удостовериться в наличии и достаточности таких полномочий.

8.6. Согласие Субъекта персональных данных не требуется для обработки его персональных данных в связи с необходимостью ответа Оператором на мотивированные запросы правоохранительных органов, органов прокуратуры, безопасности и иных органов, уполномоченных запрашивать информацию в соответствии с законодательством Российской Федерации.

9. Права Субъектов персональных данных и взаимодействие с Оператором

9.1. Каждый Субъект вправе получать для ознакомления свои персональные данные и требовать от Оператора их уточнения, блокирования или уничтожения в случае, если персональные данные являются неполными, устаревшими, неточными, незаконно полученными или не являются необходимыми для заявленной цели обработки.

9.2. Субъект персональных данных вправе получать информацию, касающуюся обработки его персональных данных.

9.3. Субъект вправе отозвать свое согласие на обработку персональных данных в любое время следующим способом:отправить письмо в наш офис в России.

9.4. Субъект персональных данных имеет право на защиту своих прав и законных интересов, в том числе, на возмещение убытков и (или) компенсацию морального вреда в судебном порядке.

9.5. Субъект персональных данных вправе вносить изменения в предоставленные Оператору персональные данные путем направления обращения Оператору по адресу: privacy@alltech.com.

9.6. Субъект персональных данных вправе обратиться к Оператору с запросами, предусмотренными в п.9.1. настоящей Политики следующими способами: – путем обращения к Оператору по телефону+7 495 258 25 25; – путем направления письменного обращения Оператору по адресу:privacy@alltech.com.

9.7. Субъект персональных данных вправе отказаться от получения маркетинговых материалов в любое время путем: – перехода по ссылке, включенной в каждое маркетинговое сообщение, направляемое Субъекту персональных данных; или – посредством направления соответствующего запроса в любое время по адресу электронной почты privacy@alltech.com.

9.8. В случае отказа от получения маркетинговых материалов Оператор продолжает обрабатывать персональные данные Субъекта, если при этом сохраняются основания для их обработки.

10. Сведения о выполняемых Оператором требованиях к защите персональных данных

10.1. Защита персональных данных, обрабатываемых Оператором, обеспечивается реализацией правовых, организационных и технических мер, необходимых и достаточных для выполнения требований законодательства в области защиты персональных данных в России. Конкретные меры, применяемые Оператором, закреплены во внутренних документах Оператора и могут быть предоставлены по запросу.

10.2. Меры, осуществляемые Оператором, определяются с учетом применимого к Оператору законодательства.

10.2.1. Избирая указанные меры, Оператор принимает во внимание положения ст.18.1 Закона о персональных данных, которые, в частности, могут включать следующее:

– назначение Оператором ответственного за организацию обработки персональных данных;

– издание документов, определяющих политику Оператора в отношении обработки персональных данных, локальных актов по вопросам обработки персональных данных, а также локальных актов, устанавливающих процедуры, направленные на предотвращение и выявление нарушений законодательства Российской Федерации, устранение последствий таких нарушений;

– применение правовых, организационных и технических мер по обеспечению безопасности персональных данных в соответствии со статьей 19 Закона о персональных данных;

– осуществление внутреннего контроля и (или) аудита соответствия обработки персональных данных Закону о персональных данных и принятым в соответствии с ним нормативным правовым актам, требованиям к защите персональных данных, политике Оператора в отношении обработки персональных данных, локальным актам Оператора;

– оценка вреда, который может быть причинен Субъектам персональных данных в случае нарушения законодательства о персональных данных, соотношение указанного вреда и принимаемых Оператором мер, направленных на обеспечение выполнения предусмотренных законом обязанностей;

– ознакомление работников Оператора, непосредственно осуществляющих обработку персональных данных, с положениями законодательства Российской Федерации о персональных данных, в том числе требованиями к защите персональных данных, документами, определяющими политику Оператора в отношении обработки персональных данных, локальными актами по вопросам обработки персональных данных, и (или) обучение указанных работников.

10.2.2. Избирая меры по обеспечению безопасности данных, Оператор принимает во внимание меры, указанные в положениях ст.19 Закона о персональных данных, которые могут, в частности, включать следующее:

– определение угроз безопасности персональных данных при их обработке в информационных системах персональных данных;

– применение организационных и технических мер по обеспечению безопасности персональных данных при их обработке в информационных системах персональных данных, необходимых для выполнения требований к защите персональных данных, установленных Правительством Российской Федерации;

– применение средств защиты информации, прошедших в установленном порядке процедуру оценки соответствия;

– оценка эффективности принимаемых мер по обеспечению безопасности персональных данных до ввода в эксплуатацию информационной системы персональных данных;

– учет машинных носителей персональных данных;

– обнаружение фактов несанкционированного доступа к персональным данным и принятие мер;

– восстановление персональных данных, модифицированных или уничтоженных вследствие несанкционированного доступа к ним;

– установление правил доступа к персональным данным, обрабатываемым в информационной системе персональных данных, а также обеспечение регистрации и учета всех действий, совершаемых с персональными данными в информационной системе персональных данных;

– контроль за принимаемыми мерами по обеспечению безопасности персональных данных и уровня защищенности информационных систем персональных данных.

11. Заключительные положения

11.1. Обязанности и права Оператора, а также условия и принципы обработки персональных данных, не упомянутые в настоящей Политике, определяются в соответствии с законодательством Российской Федерации.

11.2. Дополнительная информация относительно обработки персональных данных может быть предоставлена Оператором по запросу Субъекта персональных данных предусмотренными в настоящей Политике способами.

11.3. Проставляя «галочку» в форме сбора персональных данных, размещенной на Сайте Субъект персональных данных выражает свое полное и безоговорочное согласие с условиями настоящей Политики и подтверждает, что он должным образом ознакомлен с ней.

11.4. В случае несогласия Субъекта персональных данных с условиями настоящей Политики Субъект не должен предоставлять свои персональные данные.

Компания Alltech была основана доктором Пирсом Лайонсом в 1980 году на $10,000 и мечте. Сегодня Alltech остаётся частной компанией с выраженным чувством ответственности перед населением регионов, в которых она ведёт бизнес.

Компания Alltech считает своим долгом помогать нуждающимся. Для этого мы основали Фонд Alltech ACE, некоммерческую организацию, которая финансирует различные благотворительные начинания по всему миру.

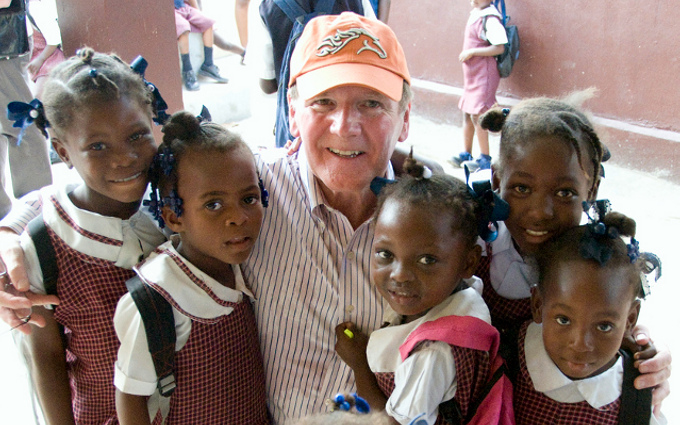

Проект устойчивого развития Гаити

После разрушительного землетрясения в 2010 году Alltech создал проект устойчивого развития Гаити в городе Уанаминт, чтобы помочь построить надёжное будущее в небольшой части Гаити. Наши усилия были сосредоточены на образовании путём улучшения и обновления школ, помощи местным предприятиям Гаити благодаря выводу на рынок гаитянского кофе и гаитянского рома, а также участию в развитие экономики страны.

На Гаити существует множество проблем, которые усугубляются природными катаклизмами. Это беднейшая в западном полушарии страна, вековая бедность проявляется в плохо построенных и поддерживаемых структурах, обширных трущобах и убогих жилищах.

Кроме того, нерациональная вырубка леса и расчистка площадей под сельское хозяйство длились более двух веков, что привело к разрушительной эрозии почв. В результате выросла частота наводнений, снизился потенциал сельского хозяйства.

Стабильный экономический рост – это ключ к долгосрочным переменам на Гаити, поэтому мы инвестируем в его будущее на самом базовом уровне.

Устойчивости невозможно добиться без образования, поэтому проект устойчивого развития Гаити включает в себя полную материальную ответственность, а также ремонт и поддержку образования в двух начальных школах на севере Гаити. Наш проект также возродил жемчужину Гаити: выращенный полностью в тени кофе арабика, который Alltech вывел на рынок и реализует под брендом Alltech® Café Citadelle.

Вместе мы помогаем построить более устойчивое будущее в одной маленькой части Гаити, создавая рабочие места для гаитян и зажигая любовь к обучению у их детей на всю жизнь.

Подробнее о школах на Гаити: https://www.alltech.com/about/philanthropy/sustainable-haiti-project

Подробнее о благотворительных проектах по всему миру:

https://www.alltech.com/about/philanthropy/involvement-projects-around-world

We are dedicated to working alongside producers in order to optimize the well-being and performance of animals, unleashing their true genetic potential through nutrition.

С помощью кормления помогаем контролировать здоровье поголовья, поддерживать стабильную продуктивность, обеспечивать прибыльность хозяйств и решать разнообразные задачи: от повышения оплодотворяемости и продуктивности свиноматок до повышения качества мяса.

Области, где мы можем быть полезны:

С помощью кормления помогаем производителям аквакультуры контролировать здоровье, поддерживать стабильную продуктивность, обеспечивать прибыльность хозяйств и решать разнообразные задачи: от усвояемости микроэлементов до укрепления иммунитета и устойчивости к заболеваниям.

Области, где мы можем быть полезны:

С помощью кормления помогаем коневодам контролировать здоровье, поддерживать активность животных и решать разнообразные задачи: от достижения идеальной кондиции до повышения воспроизводимости.

Области, где мы можем быть полезны: