Jack Bobo – How the Food Supply Chain Changed in 2020

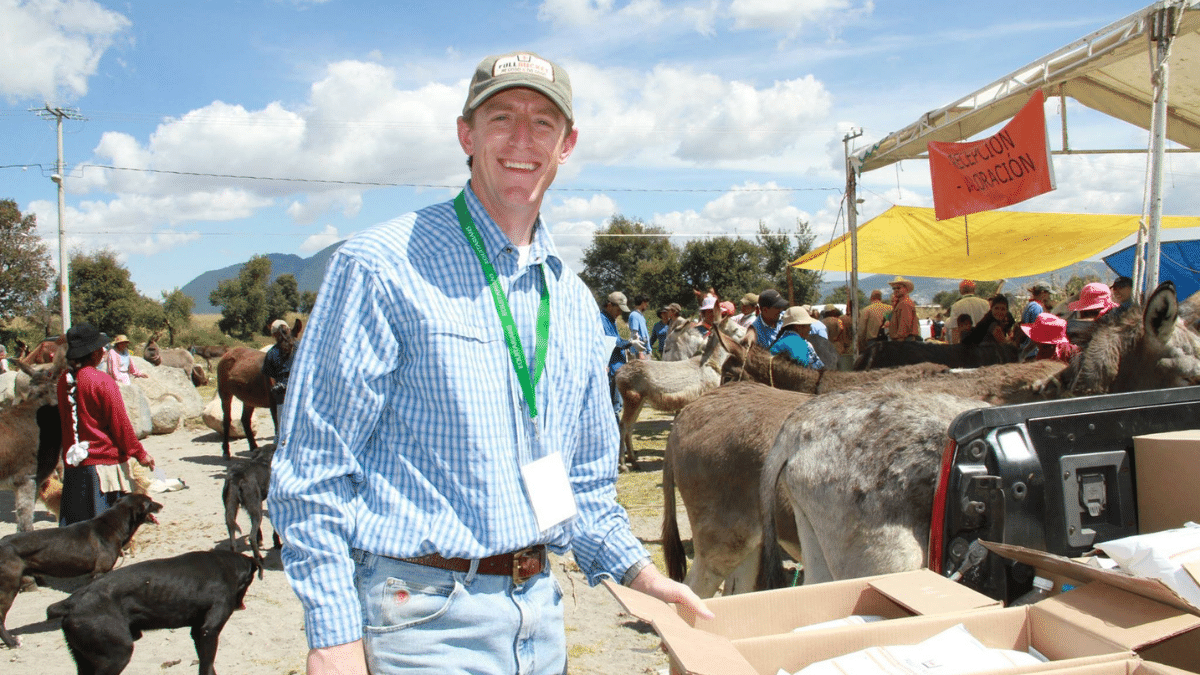

Five months ago, we spoke with Jack Bobo, CEO and founder of Futurity, about the rapidly changing food supply chain and what trends he believed would influence the future of food production and consumer habits. We recently spoke to Jack again about how consumer trends in the food industry and the food supply chain adapted through the rest of 2020.

The following is an edited transcript of the Ag Future podcast episode with Jack Bobo hosted by Tom Martin. Click below to hear the full audio.

Tom: Welcome to Ag Future, presented by Alltech. Join us as we explore the challenges and opportunities facing the global food supply chain and speak with experts working to support a Planet of Plenty.

Futurist and Futurity CEO Jack Bobo was with us back in June of 2020, when we were only beginning to come to grips with the meaning of the term “pandemic”. We wanted to know then what sorts of behaviors and trends peculiar to the COVID-19 crisis he was observing, and so much has happened since then. Jack is back to update us on trends in food and farming. Welcome to Ag Future, Jack.

Jack: Thank you for having me.

Tom: When we spoke with you in June, you were noticing an acceleration in online purchases of foods and other goods. Let's start with that. What has happened in that sector since June?

Jack: Well, a lot is happening. One thing is just (that) the numbers continue to go up. We've got about a 200% increase in shopping over that time. One thing that's interesting is that we're not nearly seeing as much loyalty, though, in the online shopping as we do to the brick-and-mortar store, so I think that's a bit of a surprise — that consumers are much more willing to try two or three or four different online stores, whereas normally, we have sort of one store that we go back to time and again, our local store.

Tom: I've heard that there is a problem now with returns through the mail and through FedEx and UPS — a phenomenon that wasn't happening before, because people were taking them back to brick-and-mortars. Are you hearing about that?

Jack: Yes. I think that's definitely an issue. There are a few issues, though. That's one, and that's an important one, and it can contribute to waste — but of course, all of this home delivery is just adding to the package waste that's becoming just an enormous problem. One thing that's a bit of a distinction is that companies like Instacart, where they're actually making local purchases and bringing it to the home, have gotten about a 50% increase (in) consumer loyalty over those that are purely online, and I think that addresses a little bit of that issue. When somebody is actually going to your local grocery store and picking it out, that's one thing, but when somebody's sending it across the internet, that feels like somebody didn't really take as much care to get it to you.

Tom: Right, and we're learning a new etiquette, a new discipline, in working with our Instacart shoppers. It's been kind of interesting.

Jack: It is. People are learning lots of lessons that they didn't expect to at this age.

Tom: Well, at the time back in June when we spoke with you, you noted that due to the pandemic, we had just compressed five to ten years of growth in online food purchases into just a couple of months. At that time, you predicted that this would have a long-term impact. Would you say that online food shopping is here to stay?

Jack: Well, the numbers are pretty good. (In) surveys that have asked people (who) are currently doing online shopping whether it's something they intend to stick with, about 90% of online shoppers today think that they will continue to make those purchases online long after the pandemic has passed.

Tom: There's been a big shift from most people dining outside of the home to most everybody now eating their food at home, and this is going to continue for some time. What are the implications?

Jack: Well, some people today are getting a little bit tired of eating the same thing over and over again and are finally accepting that they might need to learn to cook as well. So, one thing that I've noticed is an explosion in online cooking classes. People are trying to either learn some new skills or learn those skills for the very first time. I think that's going to be a good thing long after this, because people feel more comfortable in the kitchen, but other things that are coming out of this are that restaurants are trying to get in on the game as well — because people aren't coming into the restaurant, but they want to be able to connect with people at home.

This has led to a lot of restaurants creating sort of that dining experience in the home, so they're packaging up their products in a way that can then be served at home so you feel a little bit more like you're getting that dining experience than you would from just getting a meal kit. What I think that's interesting is that if COVID hadn't happened, most restaurants would not be getting out of the box. They would not be trying to explore new paths and new models to reach the consumer. They would have just continued to do things the way they had been doing it forever.

This has really shaken up the restaurant world, and those are changes that are going to stick — or some of them will. I think that we're going to find that some of them that are able to do it better are going to thrive because of this. Unfortunately, I think a lot of the smaller players, it's just going to be very challenging for them, and I think we'll continue to see a lot of small restaurants going out of business.

Tom: It's going to be interesting to see what business model emerges from this pandemic and has staying power after that happens. Earlier this year, you were talking to people about panic buying and retail therapy and then food production squeezes and shortages. So, looking forward, what are the long-term implications to our food supply and how we produce food that are going to come out of this pandemic experience?

Jack: Well, I think the first thing is just to be proud of the fact that our supply chain responded as well as it did to the pandemic. There were a lot of predictions that we were going to run out of food, that animal protein was going to be in short supply, that people were going to be rationing, and none of those things really came to pass. I think that that is to the credit of the companies in the supply chain, the food companies, the farmers and others, who all stepped up to avoid the really serious disruptions that could have taken place.

Now, absolutely, there were some disruptions of the supply chain, but given the magnitude of the problem that we faced, things certainly went better than they might have. Other things, though, to think about is that the United States is gearing up for a stimulus package that is about $900 billion, nearly $1 trillion. This is going to provide a lifeline to many people in the near term, but in the longer term, that money is going to run out as well. There are a lot of people that are in a very precarious situation today, a lot of renters who have not been paying their rent. Mortgage owners have not been paying, and at some point, those bills are going to come due. So, as well as things have worked so far, I think we're going to see people being squeezed far more on the consumer side than on the food production side, but when people don't have any money, that tends to have an impact on the entire supply chain.

Tom: How is the consumer mindset being changed, and where do you think it's going in regards to food trends? Is the way people think about food actually changing?

Jack: Well, I believe (that) last time we talked, I talked about how uncertainty over jobs, uncertainty over the pandemic, all of those things tend to make people more cautious. When people become more cautious, they become more frugal, more careful in how they spend their money. I think we're definitely seeing a lot of that. I think that those kinds of trends are not things that people get over quickly. They tend to be lasting effects. One, people are going to be short of cash for a long time, but the mental repercussions of that are going to last much, much longer.

Tom: Again, when we talked earlier in the year, it was, then, way too early in this crisis to make any definitive statements about how it would impact people across the demographic spectrum, but let's look at Generation Z: 18-to-23-year-olds (who) are coming into life with possibility before them, a lot of hope, and suddenly, that's all gone on hold. What does the future have in store for that age group?

Jack: Yeah. Well, this is definitely the group that is going to be hit the hardest and where the impacts are going to last a lifetime. My daughter started college this fall, but she started from her bedroom. I can tell you, she much would have preferred to have been on a college campus. But more than that, the students that are graduating last year and over the next few years, they'll be graduating into the worst economic climate since the Great Depression.

We know that (for) people (who) lived through the Great Depression, that impacted how they think about money, how they think about food, how they think about expenses for their entire lives. So, I think we know for sure that those (who) are in that age group that you mentioned will have really lasting effects on how they think about everything. So, we shouldn't be surprised if they come out of this being more cautious, more careful, more prudent in how they spend their money, but it's also going to have an impact on their earning potential for their entire lives, because the first few jobs you have puts you on a trajectory for retirement.

So, they're going to be starting, really, several years behind, and those are things you really just can't make up.

Tom: What would you say has COVID-19 revealed about the ways that we get the right food to the right people at the right price? What have these disruptions shown us about our food systems?

Jack: Well, on one hand, our food system is resilient, but it can be disrupted. These disruptions can have broad, even global repercussions. Some of those are going to be in the short term, but some of those will ripple throughout the years. I think the system is better if countries resist the urge to limit exports and to protect their citizens, because we have seen little where countries have been blocking exports, but where we do, those really (have the) potential to disrupt global trade, and it makes everybody nervous.

Unfortunately, the few times that that happened over the last six months have not grown and (have) become a global problem. In many ways, that was the problem we saw back in the 2008 and 2009 global recession. This is not a short-term problem. We'll probably lose a decade of progress towards things like reducing global hunger. That's very unfortunate. We had been making decades of progress at reducing hunger and poverty. Those trends are going to continue or (are) going to be reversed for years to come.

One of the challenges in 2021 is that we're going to have tens of millions of new people who are going to fall into poverty and hunger, some of them for the very first time. So, at a moment where many governments are struggling to take care of their own people, we're going to have people all around the world that are going to be in greater need, and so it's going to be a challenge to see whether or not countries can take care of their own but also recognize that there's a global need that needs to be addressed as well.

Tom: Jack, you touched on this a little bit earlier, but I'd like to expand on it, if I could. Again, in June, I asked who you saw coming out of the pandemic as winners and losers, and you singled out online purchasing as a big winner but (said that) restaurants and small businesses (are) in real trouble. What is your assessment now of sectors that will emerge strong versus those that will either not survive or will come out of this, somehow, transformed?

Jack: Well, one thing I think is interesting is that the importance of farming and food production has never been clearer. I think that's really important because I think, for too long, many consumers had taken food production for granted. Now, this is both a blessing and a curse, for our consumers to care about what it is that you do, because when people care about things, they begin to want policy changes in order to make things better. Sometimes those policy changes do, in fact, improve the situation, but there's also a risk that they'll make things worse.

I don't think we quite know how that's going to play out. But just one example is — I've heard a lot of people talking about how we need to go back to a time when there's greater inventory so that we don't run into the shortages we did at the beginning of the pandemic. I think people forget that by cutting down on inventory, what we did was we reduced cost. Now, the cost of not having inventory is that you're more at risk, but eliminating inventory also reduces cost and the price to the consumer. There are trade-offs. If we have inventory, we're better prepared for a pandemic, but those who are worried about the cost of their food may be disadvantaged. So, I think one of the challenges we're going to have is: How do we balance the need to fix some of the problems that we identified without creating new problems that we'll have to live with?

Now, in terms of winners and losers, we've already talked about online purchasing as a winner. We've talked about restaurants; many of them are going to come out of this much, much weaker. There will likely be some that benefit from it, but I think there's going to be a reassessment of the role of dining out in our lives. That's something that restaurants are going to have to figure out: how they can play a more intimate role in the lives of consumers. I think that food companies also are going to have to evaluate where they are and what their relationship is to the consumer.

Some of the winners are the larger, big food companies that had been really struggling, to be honest, over the last couple of decades to get the attention of the consumer. These days, consumers are more interested in that comfort and are turning back to the brands that they grew up with. So, I think that they're going to come out of this much stronger, and that's going to be a benefit to them for a long time to come.

Tom: Well, change is a given. It's like background noise; it's always there. It's always occurring. But right now, we're going through some monumental changes. I wonder about your thoughts, if it's possible to form some thoughts, about the market implications of the changes that are underway in Washington.

Jack: Yes. Well, I think that we're seeing a lot of changes taking place. I think that there were some that were worried about what the market implications would be of changing from a Republican to a Democratic administration. I think the stock market, at least, has not been concerned about the change, so I think there will be a continuation of positive growth there. But I expect that there will be some changes in terms of how a new administration looks at things like climate change, environmental issues, sustainability, and health and nutrition.

I think we'll see a change in focus on priorities, but I don't think that we'll see such dramatic impacts that it's something that people or companies or industries would need to be worried about. Hopefully, there's an opportunity for companies that are already interested in addressing sustainability issues to partner with the new administration in order to accelerate some of the things they're trying to do.

Tom: Futurist and Futurity CEO Jack Bobo. Thanks so much for the conversation, Jack.

Jack: It's been great. Thanks for having me.

Tom: Thank you for listening. To hear other conversations with many of the featured speakers at ONE: The Alltech Ideas Conference, visit ideas.alltech.com. Access is free after signing up.

Online shopping trends look to continue beyond 2020 as surveys have show that about 90% of online shoppers in the U.S. today think that they will continue to make those purchases online after the pandemic has passed.